In this limited-but-still-common structure, marketing has a box on the org chart reporting to the CEO. Implicit in the functions of that box are the usual marketing responsibilities like advertising, promotions, sponsorships, trade shows, direct, and database management — all the traditional elements of managing the brand.

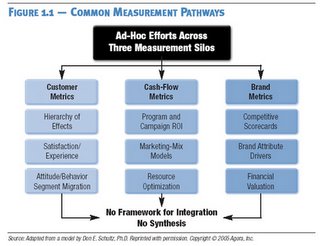

Communications programs are managed for ROI against benchmarks. Media-mix models may be employed to maximize efficiency of advertising dollars, and brand equities may be tracked to gauge progress at favorably influencing perceptions.

Chances are that few, if any, of these measures get much play outside the marketing department. Yet each year marketing budgets reflect the desire of the rest of the company to minimize marketing waste.

The new meaning of “fully integrated” for the marketing department is one that places the emphasis on active collaboration with most, if not all, other departments in the company to improve the appeal, volume, and profitability of the company’s products or services to achieve the maximum value from each customer relationship. A quick glance at the chart below will tell you how your marketing department stands with respect to other roles in the fully integrated organization.

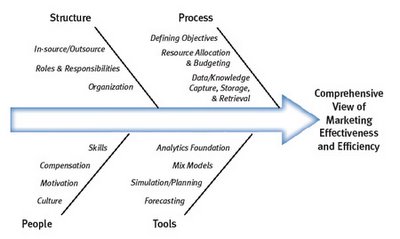

The fully integrated marketing department of today manages the brand on a much more expansive level, taking a clear role in defining and handling many aspects of the customer value proposition from product or service conception to forecasting to sales effectiveness to touchpoint experience. The fully integrated marketing department is much more likely to be linked closely with the overall organizational planning process, in many instances helping to set the strategic agenda for the entire company and establishing key cross-functional milestones like customer satisfaction, share-of-customer penetration, and perceptions of quality. It is more likely to be speaking the same language as the rest of the organization — revenues, operating margins, efficiencies, and process improvement. And the budgeting process for the fully integrated marketing department uses the company’s overall sales and strategic goals as an input variable, not an afterthought.

For those of you thinking, “Yeah, I’d like to get my marketing organization more integrated with the rest of the company and stop being the kid with the nose pressed up against the candy-store window,” be warned: Many marketing careers have been ruined when ambition and a sense of entitlement outstripped organizational ability.

Successfully integrating marketing into other parts of the organization often is not something for which other functional department heads are clamoring. It might not even be on the CEO’s list of good things to do this year. You may need to commit yourself to a slow, steady, and stealthy path of gaining the permission to contribute and building a reputation for adding value without usurping control … which is exactly where your marketing dashboard comes in.

By promoting a cross-functional approach to developing your dashboard, you demonstrate the desires to be both objective and accountable in measuring marketing performance, as well as the leadership skills to reach out to groups with whom you might historically have been in conflict. Requesting (and respecting) their perspectives in how to define and measure marketing success can illuminate the areas where your peers take a different view of the role of marketing and facilitate the dialogue necessary to bridge the gaps, or at least begin the healing.

In short, the process of developing and implementing your dashboard can be the perfect “cover” for redefining the role of marketing in the broader organizational context and further integrating marketing into the core of the business operation.