Wednesday, December 21, 2005

Can You Link Brand Ads to Profits?

Let’s say you have a tracking study out in the market in which you’ve identified 15 key brand attributes and have a sampling of customers and prospects rating your brand vs. competitors on each attribute. You also ask about self-reported purchase activity in your category. You survey 200 people each month and read the results on a rolling three-month basis.

Now, using statistical regression techniques, you can correlate brand attribute ratings to purchase activity or purchase intentions to identify the attributes that are most strongly associated with increased category or brand purchase behavior.

Simple, right? Hardly.

There are a great many places where this approach can get derailed or become seriously misleading.

First off, self-reported purchase behavior can be significantly different from actual purchase behavior. Sometimes, people forget how much they bought and which brands. Other times they tell little white lies to protect themselves from the judgment of others (even the interviewer). If you can connect a specific individual’s survey responses back to that person’s actual purchase behavior as reflected in your transactional files, you can close the gap somewhat. If not, you might check to see if there's a syndicated "panel" study done in your category where consumers respond to survey questions and share their actual receipts or credit card statements. Failing that, you can conduct a separate study specifically among a group of category consumers and check to see how self-reported behavior varies from actual purchases, then use that as an error factor to adjust what you get from your tracking studies.

Second, attributes are commonly “lumped” together by consumers into positive and negative buckets, making it difficult to see any one attribute as a real driver to a greater degree than others. This is the covariance effect — a statistical term indicating the extent to which two or more elements move in the same direction. Sometimes it’s helpful to group attributes with high covariance into “factors,” or higher-level descriptions. For example, the attributes “offers good value for the money” and “is priced competitively” might be grouped into a factor called “price appeal.” As long as you aren’t grouping so many attributes together into a few still undistinguishable factors, you can still get a strong feeling for which elements of the brand scorecard might be most important.

There are many more ways that this process can become subtly misleading. If you’re not a research professional or statistician, you might consider consulting one of each in your methodology design. But, time and again, interviews with researchers suggest that the best approaches start with sound qualitative research among customers and prospects to identify the possible list of driver attributes and articulate them in ways that are clear and distinct to survey respondents.

Done correctly, this effort can help directly link changes in attitudes or perceptions caused by brand advertising back to incremental economic value creation. But obviously it takes time and money to lay this foundation. If you're spending a few million (or more) annually on brand advertising though, it might just be worth it.

Have you been able to identify specific aspects of your brand that drive customer relationships? We'd like to hear your story.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

Forward-Leaning Metrics

Today, marketing reporting, and to some degree financial reporting, is primarily a function of gathering sales data at the end of a reporting period, massaging it into charts and graphs, and then circulating it for discussion or comment. And for most, even this is no small accomplishment.

This diagnostic approach is rooted in the instinctive human learning method of interpreting past experiences to frame future expectations. At best, that process is effective at helping the organization see where it’s recently been. Only through very intuitive methods do companies attempt to project the trajectory of performance into the future so they can manage to the desired outcome. And only a very few possess the innate (or artistic) ability to properly view diagnostic information and project it with reasonable accuracy, overcoming their own perceptual biases and assimilating the collective wisdom of their entire team. This is the fundamental human frailty marketing dashboards can help overcome.

Without a doubt, there is benefit to having diagnostic measurements on your dashboard. But without components that help you predict the future, the dashboard is only expanding the limitations of memory, not improving decision making. Think again about the dashboard on your car and how it works with your vision and stored experiences. You keep your eyes fixed on the road ahead with only quick glances at the dashboard to see how speed, fuel level, and engine stress will affect the desired outcome of arriving at your destination. Your brain makes millions of calculations per second to adjust the turn of the wheel, the pressure on the gas pedal, and the search for rest areas along the way. You might even have reviewed a map before starting out to form a mental picture in your mind of where you were going.

Today’s vehicles are increasingly equipped with some “forward-looking” dashboard capabilities. Compasses are being replaced by GPS systems that provide real-time mapping to guide you to your destination, alerting you in advance to upcoming turns. Fuel gauges are evolving to become distance-to-empty meters that display not just the current level of the tank, but how far you can go before stopping based on constantly updated fuel economy readings. By focusing your thinking on the journey ahead, these advances make driving easier and more efficient.

However, most marketing dashboard metrics are still being presented in the form of current vs. prior period. That’s helpful in terms of seeing the trend to the current point in time. But, to use the vehicular metaphor, it would be like driving forward while looking in the rear-view mirror — more than a little dangerous.

The metrics on a marketing dashboard highlighting current performance should be compared to a forecast for where they’re supposed to be at that point in time relative to the longer-term goals. That way, the dashboard answers the question, “Where is my projected outcome vs. my target outcome?” Proper marketing dashboard readings give you an indication of whether you’re on the right course, at the right speed, and have enough gas in your tank to get to your desired destination, not just any destination. If the dashboard says you’re off course, you can look at past-performance data for diagnostic insights and ideas on how to course-correct, but no longer will looking back be your central focus (or the focus of countless hours of discussions and justification exercises).

Thursday, December 08, 2005

Revenue Metrics - Bad for Credibility

The potential to be misleading is relevant in that marketing costs must be allocated to the sales they generate before we determine the net incremental profits derived from the marketing investment. If we spend $5 million in marketing to generate $10 million in sales, fine. If the cost of goods sold (COGS, fully loaded with fixed cost allocations) is less than $4 million, we probably made money. But if the COGS is more than $4 million, we’ve delivered slightly better than breakeven on the investment and more likely lost money when taking into account the real or opportunity cost of capital.

Presenting marketing effectiveness metrics in revenue terms is seen as naive by the CFO and other members of the executive committee for very much the same reason as outlined above. Continuing to do so undermines the credibility of the marketing department, particularly when profits, contribution margins, or even gross margins can be approximated.

In my experience, there are several common rationalizations for using revenue metrics, including:

- limited data availability;

- an inability to accurately allocate costs to get from revenue to profit; and/or

- a belief that since others in the organization ultimately determine pricing and fixed and variable costs, marketing is primarily a topline-driving function that does not influence the bottom line.

To the first of these, I empathize. Many companies suffer from legacy sales reporting infrastructures where only the topline numbers are available or updated with a minimum of monthly frequency. If you’re in one of those, we encourage you to use either the last month’s or a 12-month rolling average net or gross margin percentage to apply to revenue. Finance can help you develop reasonable approximations to translate revenues to profits in your predictive metrics. You can always calibrate your approximations later when the actual numbers become available.

If you suffer from the second of these, an inability to allocate costs precisely, consider using “gross margins after marketing” (revenue less COGS less marketing expenses). Most companies know what their gross margins are by product line, and most CFOs are willing to acknowledge that incremental gross margins after marketing that exceed the overhead cost rate of the company are likely generating incremental profits. This is particularly true in companies in which the incremental sales derived from marketing activities are not necessitating capital investments in expanding production or distribution capacity. In short, engage finance in the conversation and collectively work to arrive at a best guess.

If you find yourself in the third group, you need to get your head out of the sand. The reality is that the mission of marketing is to generate incremental profits, not just revenue. If that means working with sales to find out how you need to change customer attitudes, needs, or perceptions to reduce the price elasticity for your products and services, do it. Without effective marketing to create value-added propositions for customers, sales may feel forced to continue to discount to make their goals, leading the entire organization into a slow death spiral — which, ironically, will start with cuts in the marketing budget.

If you identified with this third group, this should be a wake-up call that your real intentions for considering a dashboard are to justify your marketing expenditures, not really measure them for the purpose of improving. If that’s the case, you’re wasting your time. Your CEO and CFO will soon see your true motivation and won’t buy into your thinking anyway.

Having said all that, there are some times when using revenue metrics is highly appropriate. Usually those relate to measurements of share-of-customer spending or share-of-market metrics that relate to the total pie being pursued, not those attempting to measure the financial efficiency or effectiveness of the marketing investment.

In addition, be especially careful with metrics featuring ROI. If ROI is a function of the net change in profit divided by the investment required to achieve it, it can be manipulated by either reducing the investment or overstating the net profit change beyond that directly attributable to the marketing stimulus. Remember that the goal is to increase the net profit by as much as we can, as fast as we can, not just to improve the ROI. That’s just a relative measure of efficiency in our approach, not overall effectiveness.

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

How Much Risk Is in Your Marketing Plan?

For marketing executives, risk management is a trial-and-error evolution. Has this agency produced good work previously? Will this vendor deliver on time? Experience has fine-tuned our instincts to a point where we intuitively assess risks based upon a combination of hundreds of deliberately and subconsciously collected data points.

Many executive committee members still view marketing as the last bastion of significant risk exposure. Everyone else from finance to operations, HR to IT employs robust risk-assessment tools and processes and highly effective ways to demonstrate the risk-adjusted outcomes of their key projects. They talk in terms of "net present value" of "future returns" associated with an investment made today. They link their recommendations to the bottom line and present their cases in such a way as to reassure not just the CEO, but also their peers, that they have carefully analyzed the financial, operational, organizational, and environmental risks and are proposing the optimal solution with the best likely outcome.

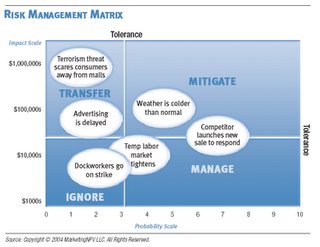

This process needs to be carried into the marketing measurement platform. Each proposed initiative or program should be evaluated not just on its total potential return, but on its risk-adjusted potential.

Here’s an example: Let’s say we’re a retailer planning a holiday sale. We plan to run $1 million of TV advertising to drive traffic into stores during this one-day extravaganza. Using the reach and frequency data we get from our media department, combined with our assessment of the likely impact of the advertising copy, we estimate that about one million incremental customers will visit our stores on that day. If only 5% of them purchase at our average gross-margin per transaction of $20, we break even, right?

Unless, of course, it rains. In that case, our media will reach far more people watching TV inside, but far fewer will venture out to shop. Or maybe the weather will be fine, but one of our competitors will simultaneously announce a major sale event of their own featuring some attractive loss-leaders to entice traffic into their stores. Or maybe there will be some geopolitical news event that disturbs the normal economic optimism of our customers, causing them to cancel or postpone buying plans for a while.

Any or all of these things could happen. It only takes one to completely mess up the projected return on the $1 million investment in sale advertising.

A strong measurement framework requires that each marketing initiative be thoroughly risk-assessed to identify all the bad things that could happen, the likelihood of them happening, and the potential impact if they did. The project forecast is then reduced accordingly. So if rain would cause a 50% drop in estimated store traffic and the weather forecast shows a 30% probability of rain in the area, our forecast for the event should be reduced by 15% (50% x 30%).

This structured risk-assessment approach will highlight investments that are more prone to external risk factors and modify their rosy expectations accordingly. In the end, high-risk, high-reward initiatives may be just what’s required to achieve business goals, but wouldn’t you rather know that’s what you are approving, instead of finding it out later when high hopes are dashed?

Friday, December 02, 2005

The Dangers of Premature Delegation

First of all, the fundamental orientation for the process starts off on an "inside/out" track. Middle managers tend (emphasize tend) to have a propensity to view the role of marketing with a bias favoring their personal domain of expertise or responsibility. It's just natural. Sure you can counterbalance by naming a team of managers who will supposedly neutralize each others' biases, but the result is often a recommendation derived primarily through compromise amongst peers whose first consideration is often a need to maintain good working relationships. Worse yet, it may exacerbate the extent to which the measurement challenge is viewed as an internal marketing project, and not a cross-organizational one. Measurement of marketing needs to begin with an understanding of the specific role of marketing within the organization. That's a big task for most CMOs to clarify, never mind hard-working folks who might not have the benefit of the broader perspective.

Second, delegating elevates the chances that the proposed metrics will be heavily weighted towards things that can more likely be accomplished (and measured) within the autonomy scope of the marketing department. Intermediary metrics like awareness or leads generated are accorded greater weight because of the degree of control the recommender perceives they (or the marketing department) have over the outcome. The danger here is of course that these may be the very same "marketing-babble" concepts that frustrate the other members of the executive committee today and undermine the perception that marketing really is adding value.

Third, when measurement is delegated, reality is often a casualty. The more people who review the metrics before they are presented to the CMO, the greater the likelihood they will arrive "polished" in some more-or-less altruistic manner to slightly favor all of the good things that are going on, even if the underlying message is a disturbing one. Again, human nature.

The right role for the CMO in the process is to champion the need for an insightful, objective measurement framework, and then to engage their executive committee peers in framing and reviewing the evolution of it. Further, the CMO needs to ruthlessly screen the proposed metrics to ensure they are focused on the key questions facing the business and not just reflecting the present perspectives or operating capabilities. Finally, the CMO needs to be the lead agent of change, visibly and consistently reinforcing the need for rapid iteration towards the most insightful measures of effectiveness and efficiency, and promoting continuous improvement. In other words, they need to take a personal stake in the measurement framework and tie themselves visibly to it so others will more willingly accept the challenge. There are some very competent, productive people working for the CMO who would love to take this kind of a project on and uncover all the areas for improvement. People who can do a terrific job of building insightful, objective measurement capabilities. But the CMO who delegates too much responsibility for directing the early stages risks undermining both their abilities and their enthusiasm -- not to mention the ultimate credibility of the solution both within and beyond the marketing department.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

The Value of Knowing

When I hear those trigger words, my mind immediately goes to the response question: "What would you do with the information if you had it?"

There are two reasons the response question is so important prior to answering the original question.

First, the answer to the response question will help me understand the extent to which your organization has developed a thoughtful (if executionally challenged) perspective on critical metrics, or if you're still in the mode of identifying the superset of all possible things that might be measured.

Second, the answer will tell me the relative importance of the particular piece of information you're looking for and give me some sense of the economic value of having better certainty of knowledge. If having the knowledge will improve your business outcomes just marginally or not at all, we can pretty quickly agree that it doesn't really matter how we'd measure it. Conversely, if the expected economic value of knowing is significant, many possible doors open in terms of collection avenues, since we can presumably allocate a fair amount of resources to acquiring the knowledge and still show a very positive return on that investment.

Third (yes, I know I said there were only two, but it's a blog so cut me some slack), if your answer to the response question doesn't properly anticipate how having the knowledge would impact current decision processes, it's a sign that we need to lay some organizational groundwork before we even ask for the resources to go get the knowledge.

As you might imagine, most people are initially stumped by the response question. But if you think about your hairiest, most formidable measurement challenges in the context of the economic value of knowing, you really begin to define your priorities for knowledge aggregation.

Everything can be reliably measured -- somehow. The critical parameters (as in most business pursuits) are how much time, money, and political capital you're prepared to spend to acquire the knowledge. You can't possibly know what your tolerances are until you have some clarity on the value of knowing.

Friday, November 25, 2005

Measure What You SHOULD, Not Just What You CAN

Hmmm. Good point. Very pragmatic. Or at least that was the initial reaction of most of his teammates in the room.

But let's think for a minute about the implication of only measuring what we have data for.

- In all likelihood, we don't have much insight into the data streams we have today, or we wouldn't be talking about assembling a dashboard in the first place.

- The "spotty" data we have today leaves significant gaps between what we know, what we don't know, and most importantly, what we don't know we don't know.

- Keeping our dashboard framed within the parameters of what we already have data for is a sure fire way to reinforce every preconceived notion we have about the business.

I'm all for pragmatism. Nobody is helped by a theoretical marketing dashboard. But the very process of planning a dashboard is intended to draw out all of our structured knowledge, scientific hypotheses, and experiential best-guesses about what happens to sales or profits when we add/change/delete marketing investments. Only by looking at the business from the perspective of "what should we be measuring" and setting the framework for a truly comprehensive view of effectiveness and efficiency can we really assess what we know and where we should prioritize our search for more knowledge.

Fact: Most marketing organizations spend far too much time and precious resources answering questions that don't generate any significant insights into the business. Laying out the complete picture of what you think you need to know first is the best way to keep your marketing measurement efforts from returning the same old knowledge with the same critical insight gaps.

It makes better sense to start with what you want to know, prioritize the pursuit of the unknowns on the basis of expected insight value, and fill in the gaps in your dashboard over time. But let everyone see the gaps as a reminder of how little we actually do know and a reassurance that we, the marketers, are diligently working to try to close those gaps. It will make them feel better about our search for objective insight.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

Peter Drucker – Our Thanks

The first is management by objectives. The concept of setting objectives and allowing teams to work toward them is now commonplace, but before Drucker, command and control reigned. We at MarketingNPV cannot imagine doing our jobs without the discipline of MBO already in place. In fact, measurement of progress towards marketing objectives is much of what we do.

The second great insight we use every day to help clarify marketing’s role within a company. Drucker wrote, "Business, because its function is to create and sustain a customer, has only two purposes: Marketing and Innovation. Everything else is an expense." Many well-established companies undervalue both elements because they are living of the franchises created by earlier marketing and innovation. Success often boils down to how well the company tends its brands and customer franchise. And without measurement, marketers are hobbled in their ability to make the most of the assets under their care.

Pete Drucker may no longer be with us, but his work lives on in almost every business person every day.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

5 Magic Metrics

The more we talked, the more clear it became to her that getting down to the 5 Magic Metrics would take a diligent effort of experimentation and elimination, perhaps starting with 40 or 50. The appropriate metaphor was the old story of “I’m sorry this letter is so long, I didn’t have time to write a shorter one.” The risk of jumping too fast to the logical 5 is that you might select the wrong ones and achieve the wrong goals in a very efficient and effective way.

If you want to get down to the right 5 (or 4 or 6 or however many) metrics that really forecast success, you owe it to yourself (and your CEO) to undertake a thorough exploration of the 30 or 40 hypotheses that would emerge from a cross-functional assessment of “what really drives the business.” You’d probably not be surprised at the lack of consensus within even the best-managed companies on which 30 to even start with.

From there, it takes a bit of effort to acquire the data to test each of them for diagnostic and predictive ability, or to develop a proxy approach for the inevitable majority of metrics where the data doesn’t exist. Not that it can’t be done quickly (read: a few months), but it does require a deliberate effort.

So whenever I get the CMO request for “the 5 magic metrics,” I agree with them that it’s a great idea to strive for simplicity and to align your marketing measurement framework or dashboard to reinforce the company’s specific goals. But I also advise them to be careful about how they issue that direction to their teams, lest they create the impression that they’re only interested in simplicity (which might be interpreted as superficiality), or they send the message that speed is more important than accuracy. They’re both important.

Start with a hypothesis on what the 5 key metrics might be on the highest level on your dashboard, but don’t sacrifice the real insight derived from exploring the broader spectrum of options and validating your hypotheses. The difference will be measured in the credibility and longevity of your measurement plan.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Marketers Turning to MOM

Importantly, there seems to be a strong understanding amongst markops types that technology is best applied to automate sound business processes and to improve the suboptimal ones constrained by the limits of human processing speed, volume, or accuracy. It’s refreshing to note that this new breed of marketer is pushing automation and technology NOT for the sake of technology or job security (although they do seem to take the measure of one another through subtle clues inherent in the answer to “Which MOM platform are you running?”), but rather in the context of process improvement.

While a few of the markops folks I’ve met have been imported into the marketing department from IT or operations, most seem to share marketing or brand management DNA -- which makes them uniquely capable of envisioning the desirable outcomes of process improvement, not just the process of improvement itself. A high percentage of them are Six-Sigma-trained -- even if their current employer isn’t a Six-Sigma company. Many of the initiatives they’re undertaking are targeted at goals like more efficient e-mail marketing, Web site customization, customer datamart assembly, and integrated campaign optimization. There’s even some discussion of ROI -- albeit mostly still in the context of paying for the investments in the technology.

I think this is a very positive trend for marketing measurement and accountability. Focusing on process and information flows will accelerate the appetite for reliable measurement structures. My hypothesis is that the more tactical focus of the markops function of today will evolve into a more strategic one as the low-hanging fruit of process improvement is picked and the organizational confidence in them grows. In the future, I would expect their unique perspective within the department to translate into leading roles in architecting marketing measurement platforms. Provided, that is, that they can maintain direct access to the CMO, and that they are appropriately skilled in continuously reinventing their job descriptions to consolidate past successes and build bridges across functional groups within the marketing department. But that’s a message that the CMO needs to hear too.

If you’re in marketing operations today, I’d like to hear your perspective on the challenges and opportunities.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

Brand Measurement Mayhem

Many billions of dollars are spent in this country researching and tracking brand equity, most of it through approaches that attempt to carefully dissect the individual image attributes, emotional connections, and perceptions of our companies, brands, or sub-brands. But so little of it is done in a way that inspires confidence amongst CEOs or CFOs that if we increased our ratings on “trustworthy” or “innovative,” we’d see significant improvements in financial results.

Perhaps because there are so many opinions and methodologies about how to correlate changes in key brand equity components to financial outcomes, the lack of consensus, epitomized by multiple vendors extolling their unique, proprietary systems, is possibly ENCOURAGING CFOs to believe that it's all just marketing babble and underscoring the soft, unpredictable nature of it.

Here’s a thought … What if we invited all purveyors of brand equity measurement processes to present their approach and case studies to an independent panel of financial executives, Wall Street analysts, and academics? The panel would then judge the merits of each approach in a fully informed context and propose standards that incorporated best-of-breed methods in a variety of “classes” aligned to the needs of different industry group dynamics — retail, financial services, packaged goods, electronics, automotive, etc.

This approach might actually help close the gap between the marketers and the financial community, moving one or the other towards a better understanding of the inherent challenges of the task and building a better framework for measurement evolution.

I’m not sure the research companies would line up to participate. Ad agencies might hate the idea too.

What do you think?

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

The Mother of All Models

What I’m referring to is a tendency I see quite often in corporate America to “crack the code” on marketing measurement by building the world’s biggest regression model.

While admirable in their pursuit, companies that seek to answer the question “What are we getting in return for our marketing investment?” with a number, i.e., “41% ROI,” are headed into a long, dark alley with a penlight. Their chances of getting to a numerical answer with any high degree of confidence is about the same as their chances of finding a specific grain of sand on the ground in that alley.

Along the way, wonderful things are learned about correlations between marketing stimulus programs and business outcomes, most of it negative. In fact, the real value that model-seekers derive is a much higher level of clarity on what doesn’t work. So there is some value to pursuing it. But outside of some packaged goods categories with clearly defined and mature purchase patterns and competitive environments, this approach rarely results in anything close to a perfect prediction of economic outcome in relationship to changes in marketing investments.

The real question is, what is the real question? You see, if you’re trying to ascertain the optimal level of advertising spend to maximize either short-term profitability or ROI, you certainly can build some effective analytical approaches to get to a reasonably small range of uncertainty (a.k.a. high degree of confidence) in an answer. Marketing-mix models can be quite helpful in answering this and similar questions.

But if you’re trying to answer the more common CEO question, “What would happen if I spent twice as much on marketing or half as much?” the answer tends to elude the power of pure analytics absent years of detailed transactional data and previously determined influences of external variables like interest rates, housing starts, demographic mobility, etc.

The bigger the question, the more likely you are to need to a comprehensive combination of marketing metrics to assemble the preponderance of evidence, like a marketing dashboard. Using insights you gain from analytics plus test/control experiments plus research plus some structured forecasting techniques, a marketing dashboard helps focus the company on what it knows and, by definition, what it doesn’t know. Over time, the key questions are identified, researched, and answered.

In short, if your inclination is to try to tackle broad questions of marketing measurement through advanced modeling techniques, you’ve only got part of the solution. Using the full set of tools at your disposal to complement your analytics will enhance your overall ability to answer the really hard measurement questions with greater credibility.

If you’ve had any experience with a modeling-centric approach to marketing measurement, please share it with the rest of us.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Never Again

“I will NEVER AGAIN go through such a convoluted, sloppy, opinion-driven process of requesting marketing resources and subjecting myself to the eye-rolling, sighing, smug resistance of finance. Next year, I WILL have more factual insight and disciplined measurement structure on my side.”

Great! Now it’s time to get started. Right now.

Not because the pain is still fresh and the motivation high (although that might actually help), but because it will take you a year to develop, validate, and properly stakeholder an effective marketing measurement process. So if you start now, you might just have something in place that makes the process much more collaborative and rational in the fall of ’06.

Some of you might be asking, “Why does it take so long?” The answer is that no effective marketing measurement system is a simple mathematical exercise. The issues are complex; the necessary information and data flows are rarely in place at the start; and there WILL be a number of assumptions that need to be made in the absence of a perfectly reliable algorithm. Not to mention that there may not even be any clear alignment across the organization on what the role of marketing is and what would constitute the definition of “success” in measuring marketing effectiveness.

On the other hand, others out there may be thinking that it’s ambitious to expect to build a comprehensive measurement structure or marketing dashboard in just nine months or so. Perhaps. But if you start with alignment amongst key decision makers on exactly what you’re trying to measure, you can begin to build and deploy your measurement process in stages — bringing modules into play as they are developed and instilling a greater sense of confidence and anticipation as you go. Don’t underestimate the credibility to be gained from just scoping the task and beginning to show progress.

So if the planning process has gotten the best of you this year, start now to ensure you get on a more level playing field next year. Once you’ve sized and scoped what it will take to really create a credible measurement process, you’ll be glad you started early.

Anyone have any experience to share on how long it took them to get a workable measurement framework in place, or how long they’ve been working on it so far?