- Setting performance metrics beyond the span of control: Keeping everyone’s eye on the bottom line is good. Linking too much of their bonus or merit consideration to key performance indicators based on financial outcomes too far removed from marketing influence, isn’t. It often results in a demoralized marketing team that is resentful of other functional departments and less likely to seek input or build consensus when it comes to strategy development, program execution, or measurement.

- Letting the metrics become the objectives: One of the big automotive components suppliers challenged its team to build a car-door hinge system that was significantly more smooth and quiet than the current approach. They succeeded. But, the cost per door tripled. If you’ve hired smart people, be careful how you state their objectives. They will find a way to achieve them.

- Impeding the flow of bad news: Metrics in marketing won’t work unless they promote objectivity — which means accepting the bad with the good. Equating reward solely with success sends the clear signal that being the messenger is a good way to get shot unless all the news is good. Find subtle ways to reward truth along with success, and link the two together in the minds of your team.

- Delegating measurement strategy: In selecting the right marketing metrics, the decision maker has to have not only a big-picture perspective, but the clout to negotiate marketing’s new science with the rest of the organization. Mid-level managers can’t do this. Only a person at the top can assess how much change marketing can take in one step and in which direction the group must move. Plus, when measurement strategy is delegated, truth and insight often take a back seat to rationalization and justification. Measurement requires leadership that ensures that every person in the organization is focused on being creative, being supportive, taking initiative, and performing as a team player. Appointing a trusted staff member to be the chief of the measurement police is a sure way to cut them out of the informal communications channels where the real information is shared. You may decide to have someone coordinate the process, but the actual measurement (and results) should be owned by a broad group of marketing leaders, chief among them the CMO.

- Allowing IT to control the agenda: In an increasingly data-driven marketing era, IT is responsible for collecting and storing data, mining customer transaction files, and sending and receiving messages in record time. Consequently the path to progress in marketing measurement is often dependent upon the same time- and resource-starved IT people who support all the other mission-critical company functions. But the prioritization of those IT resources is most often made with an eye toward fixing holes in cash-flow management or operations support, not marketing process improvement. Consequently, marketing must be prepared to present its case by simultaneously forecasting the business value of the proposed changes and the cost of outsourcing the work. In larger marketing organizations, it often makes sense to have an IT liaison on the marketing team whose responsibility includes the mid- and long-range planning of company IT capabilities to support marketing evolution and to translate the inevitable “we can’t do that” IT response into creative solutions for progress.

- Neglecting to give researchers and analysts respect: When was the last time you met a CMO who rose up through research? Researchers and analysts typically live at the lower end of the marketing pay scales and often have no career path. They need to act as thought leaders within the organization, leveraging the thought and data models they build in marketing and in all of the business functions it touches. When researchers rise as thought leaders, they encourage the use of facts and data to make smart decisions. So the smart CMO will see that these people get the training in communications skills and leadership development to expose their talents more broadly and spread that discipline within the department. It’s time to rethink the role of research and decision analytics in our marketing structures, not just expand on the same old models.

- Forgetting about training in measurement: And we wonder why we hear so much complaining about skill shortages. Survey after survey on improving marketing measurement cites the No. 1 CMO need as “getting the right skills in place.” But by our observation, fewer than one in 10 mid-to-large-sized marketing departments have comprehensive skill-building programs.

Monday, February 27, 2006

7 Organizational Obstacles to Marketing Measurement

Monday, February 20, 2006

Ideas for Channel Management Metrics

Channel Coverage

If you’re selling wireless phones through independent retailers, you’ll want to make sure you’re covering all the places where people are buying those phones. Companies that manage their distribution chains contractually — through independent agents, sales representatives, or other partners that help them get business done — can get clarity on prospect reach and market penetration from a dashboard metric on this issue. It can be even more forward-looking if coverage incorporates prospective channel partners in various stages of finalizing agreements and building out facilities.

Channel Relationship Mix

With the level of decentralization and outsourcing in business today, companies may not have full control over the players who staff their distribution channels downstream. Major oil companies like Shell and ExxonMobil don’t manage every stop on their distribution chains anymore, but they still have to keep track of how their products are selling at the consumer level. Monitoring the evolving mix of channel relationship types helps to keep the focus on the strategic importance of channel leverage strategies.

Relative Channel Performance

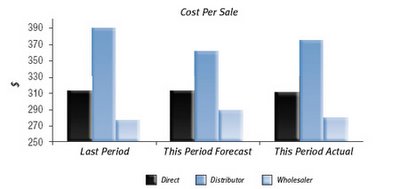

When you have multiple types of channels, you can often structure ways to look at marketing returns by channel — which gives you a view toward opportunities to optimize investments across channels. You might, for example, find that the cost-per-sale in one channel is significantly lower than the others. This raises the question of how much more money could be spent in selling through that channel before the returns begin to diminish (an optimization challenge). Monitoring these relative channel performance measures can provoke key questions about how resources are being allocated and help forecast the need for revitalizing efforts or planning capital investments.

Channel Stock Positions

Stock-outs can be a critically limiting factor to growth. Customers get annoyed when they go out of their way to come in only to find you’re out of something they think you should have. The loss can be permanent. If monitoring and forecasting in- and out-of-stock ratios is crucial to your business, then it’s relevant for your dashboard. The forward-looking component of this measurement relies on good sales forecasting to help you spot problems with your inventory before they happen. It can also help you better manage the range of merchandise you carry and watch your inventory turns more closely.

Channel Perceptions of Marketing

There’s been very little dashboard activity in this area to date, but this is a measurement category worthy of careful consideration. Many of the same companies that spend millions on research to understand customer and employee views spend nothing on capturing channel perspectives. This is not only crucial to businesses like fast food franchisors and automobile manufacturers who must coordinate local marketing activity with regional co-ops of franchisees, but can be equally important to manufacturers of all types selling through Lowe’s, Target, or other retailers for which the opinions of the category buyers and the sales floor associates can make or break marketing effectiveness. It’s also important to industries that distribute through agent networks, wholesalers, or independent sales organizations.

Channel Power Measures

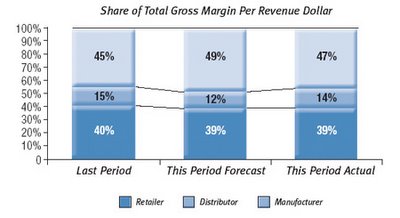

There are a number of different ways you can measure channel power, but the most compelling is how much margin you’re keeping vs. your channel partners. If the markup to the final consumer is greater than the wholesale markup, it stands to reason that you have ceded some significant power to the channel. Reclaiming some of that margin is a worthy pursuit for marketing and monitoring and forecasting channel power gives you some sense of how effective you are at changing bottom-line performance through brand building or product innovation.

These are just a few examples of how you might better reflect channel performance in your business and manage towards target goals. The old saying that "if you can't measure it, you can't manage it" might never have been more true than with respect to channel management.

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Hierarchy of Effects - BS or Baseline?

Awareness › Interest › Desire › Action

In the 1960s, the model was refined and relabeled as the Hierarchy of Effects (HOE), founded upon the assumption of a three-stage process underlying consumer purchase behavior:

“Cognition” represented the process of becoming specifically aware of a solution to fit one’s need; “affect” was the process of becoming emotionally engaged in the purchase; and “behavior” was the resulting purchase.

Over the past 40 years, all this has proven time and again to be wrong. So why is it still potentially so valuable?

The HOE model may be right for some categories and some consumers at some points in time, but it fails miserably as a predictor of how most people buy in most categories most of the time. It assumes a sequential linearity of the buying process that just doesn't hold in many (if not most) occasions. True, you are unlikely to buy something you are not aware of. But, you might just become aware of it by seeing it on the shelf at the checkout counter and decide, on impulse, to pick it up. No emotional bonding required.

But the real value of the HOE model to marketers isn’t in its accuracy as much as its existence. The mere fact that we have such a model as a starting point to begin to consider how our own categories work is very valuable. Diagnosing the linear or non-linear stages of progression amongst our own customers can be highly beneficial in forcing us to think “outside-in” from the customer perspective. It encourages us to map out the models that work in our own business, see where the critical prospect/customer progressions might be, and better understand what causes those progressions to work or what obstacles prevent them.

HOE is also a good starting point for defining and dimensionalizing segmentation strategies. If you can identify certain types of customers who employ variants of the HOE model in making their purchases, you have by definition identified discrete segments which might be targetable through efficient, albeit very different means.

Finally, HOE as a starting point helps facilitate the discussion about critical predictive metrics for measurement purposes. If you can describe and validate the buying model for a given segment of customers, it stands to reason that by closely monitoring the stage-gates at the front-end of the cycle you might reasonably predict the resulting levels of purchase behavior and a timeframe for their occurance.

Have you identified your customer progression points? How did you begin the process? Share your thoughts …