The surest way to realize the role of marketing you seek is to begin with the right vision. That means dissecting the customer value chain and finding all the places where marketing can and should play a role in improving it. But before you launch headlong into such an initiative, here are some thoughts on common pitfalls that await...

4 Ways to Lose Your Way

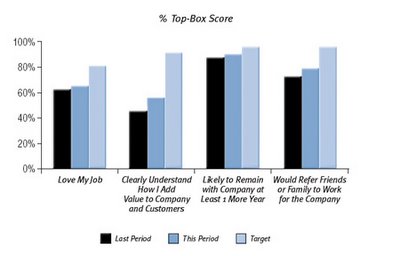

- Losing track of your base. Before you seek to expand into new areas of influence, make sure you have strong process and people managing the current scope of marketing responsibilities. You’ll also need strong measurement abilities to get early warnings of problems within the marketing department. Identify the biggest risks to your present activities, and develop mitigation strategies for each. You can’t open new frontiers while fighting wars on the homefront.

- Sticking your nose where it isn’t welcome. Before you leap to conclusions about how something outside your traditional scope can be better, ask the people managing that part of the company. Find out what worries and frustrates them. Ask them how they measure success, and see if there are more customer-centric ways of doing so that engage them. Use your credibility and capacity in customer research to help them achieve their goals. If they perceive that your interest is motivated by self-aggrandizement, you can forget about cooperation. The door will close hard, and your swollen nose will be on display for the rest of the company to see. Ground your interest in achieving measurably better results for everyone. It’s a difficult entreaty to resist.

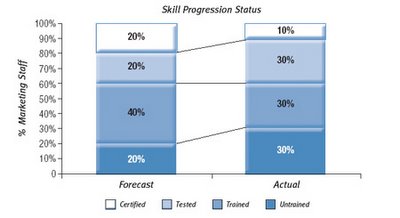

- Stretching your skill supply lines too far. Apart from the two gaffes listed already, the biggest mistake in seeking to expand influence is to get enthusiastic support from other functional heads and deliver well-meaning under-execution a few months later. The skill set of your staff must align with the value-added tasks for which you volunteer or your weaknesses will show themselves quickly. If you’ve taken the time to diagram where in the company you would like to get involved, take a few extra weeks to think through the skills necessary to succeed and your ability to get them into your arsenal either through hiring of staff or consultants or development of existing employees. Many times the reason the value-added activity isn’t being done (or done well) is because the current manager doesn’t have the requisite skill set on his or her team. Jumping in before sizing the challenge properly can make for a particularly unpleasant experience for everyone involved.

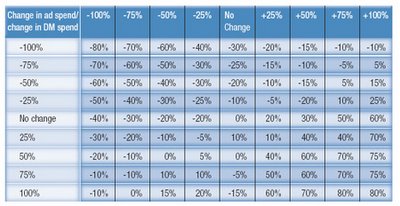

- Dying by scope-creep. There’s only one real downside to success: popularity. Once you’re successful at creating value across many areas of the organization, the risk changes to one of having such a great reputation for results that everyone wants your help. Before you know it, your marketing team is being pulled in so many directions that it’s spending too much time on trivial requests from newfound friends around the company and not enough on high-leverage initiatives that really drive results. Protect your focus diligently, and work with sales, operations, R&D, etc., to develop some clear rules of engagement marketing.

Setting Priorities to Succeed

Once you’ve mapped out a path that avoid the pitfalls, prioritize your opportunities on the basis of the likely impact on business results and the anticipated receptivity from the current functional owners. Your two-by-two matrix of opportunities will highlight those areas in which your approach will be received warmly. From this list build your marketing scope one step at a time, ensuring that you have the permission and capacity to succeed.